Have you missed us? We missed you. 2020 was a crummy year in a lot of ways. For one thing, the drought cost us nearly all of our rice harvest. That meant a drastic reduction in income for me and no rice for you.

At the heart of the problem was the fact that the piece of land we farm, our home farm, is generally quite wet and soggy but not guaranteed to be so. When we first created the rice project here on Burroughs Farm Road, we tried to work with the tendency of the core of the farm to collect water, and in fact we enhanced this attribute through creation of a reservoir pond of 160,000 cubic feet and berms to retain water. When water runs off over the landscape, generally after a very heavy rainstorm or after a few days of steady rains and showers, a few ditches that drain neighboring lands will fill our pond. If they flow at all, they will generally add several inches of pond depth or even fill it completely, no matter how low it was to begin with, if the storm is a strong one.

Rice seedlings in the greenhouse, lightly misted

The design goal is for the pond to retain enough runoff water see us through the “critical irrigation period” which lasts from mid-May, when we begin to flood and prepare fields, to mid-July, by which time plants are fully rooted and can thus withstand occasional drying. But acute drought during this time can hit us very hard. Our math depends on the pond getting replenished at least once during that 8 week period, because that 160,000 cubic feet can get used up quite fast spread out over five or more acres.

In 2018, water was very tight but we pulled off a good crop. 2020, however, did us in almost completely. Roughly 3 acres of rice withered and died, as we diverted dwindling water reserves to irrigate the best 2 acres . But even then we couldn’t maintain water levels high enough in these fields, and three-quarters of that area was also effectively lost (the ducks can only do so much!). However, one-half acre of rice was saved through a backbreaking campaign of hand weeding in the July heat, ensuring that at least we’d have enough seed to continue, even though the greater part of the season was basically up in smoke. There’s no crop insurance or any other kind of security for this kind of farming. We’re working without a net.

A mini truck full of rice transplants heading off to the paddies!

So, I did not have a great year last year. Therefore if you need another reason to look back in 2020 with distaste you may add this to the list. But farming is an act of eternal optimism. In the bleakest defeat is something to learn and grow from.

Hard as it was to accept, I came to realize that our home farm has unacceptable vulnerabilities that we just can’t correct. So I started to look at neighboring parcels, with a hopes of growing rice there, whether we have the privilege of owning them or not. There are parcels of land here and there in our town and neighboring towns, some much more suitable for rice than the only-somewhat-suitable farm I happened to buy back in 2006. Of course I didn’t know then that I had a future as a rice farmer!

We first planted rice in 2010 at our home farm in tiny hand-dug paddies and harvested 20 pounds our first year. We’ve had good years and bad, but even the bad years left me with some lesson about how I could improve and avoid pitfalls. Time and again I have doubled down on this idea of growing rice in the Green Mountain State. Over 10 years in, with so much hard-won experience gained I couldn’t allow myself to quit, though it’d be dishonest to say the idea did not cross my mind. One advantage I had as I sought a new plot was that the experience of field engineering here over many years had taught me exactly what land characteristics you need to create the best possible rice plot for the least effort. Eventually, I found a plot that met my criteria.

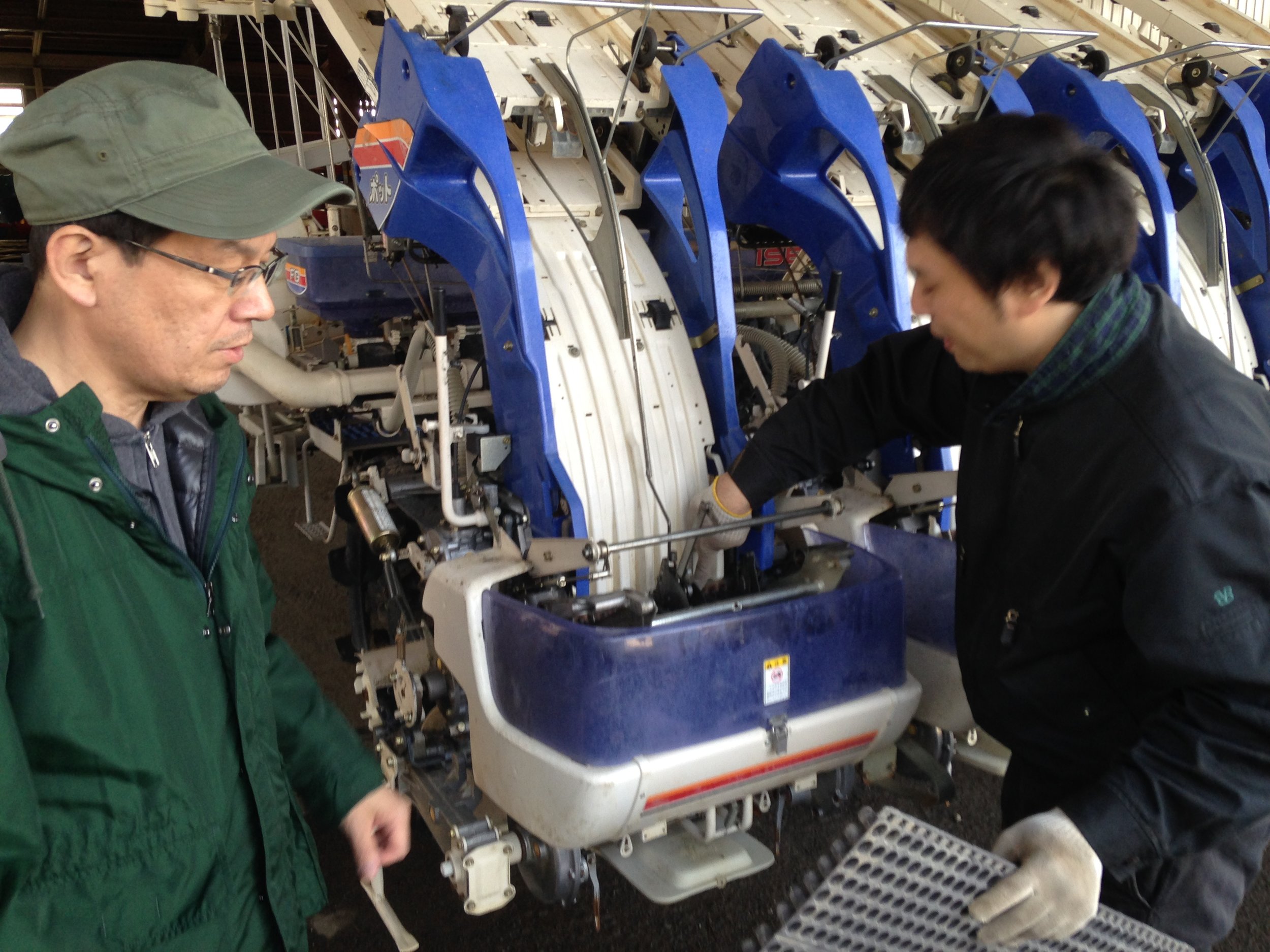

And so I signed a lease with a local landowner early this year and my new helper, Tess Clarkin and I surveyed the land and established a brand new rice paddy system on the banks of Little Otter Creek in New Haven, Vermont, 10 minutes drive down the road. It’s a little odd commuting to work rather than just walking out the back door, but I guess I’ve gotten used to it. We have a state water permit that allows us to draw from the river, which even at the lowest possible levels, can support our few acres of rice, so no reservoir is needed here. When the wind is still you can hear the water gurgling through the channel. It’s a great comfort.

Rice transplants starting to grow, grow, grow in the paddies!

Even better is the fact that the riverine soils of our new plot have a fertility edge over our soils at home, and we get to share our work environment with the river wildlife, including snowy egrets, great blue herons, night herons and wood ducks!

I won’t lie, it’s been an insane amount of work. Long hours, endless breakdowns, vehicles stuck in mud. Well, I guess all that is pretty usual. You have to be a bit different to love this kind of job. But love it we do.

Now we’re just weeks out from bringing the crop home. I can’t wait to share it with you.

A full, beautiful set of rice panicles.